Subscribe to our Newsletter to receive the latest updates on our content. By tapping the “Subscribe” button you will be redirected to subscription page. Subscription is free.

In our previous alert in the Carbon Market Series, The Climate Change (Amendment) Act, we provided high level insights into the Climate Change (Amendment) Act, 2023 (the Amendment Act) which introduces and regulates the carbon markets in Kenya to stimulate the reduction of carbon emissions through voluntary contributions.

While the Amendment Act represents a significant stride in Kenya’s efforts to mitigate climate change impacts and develop a robust carbon market, there are certain gaps and shortcomings within the Amendment Act that may require further refinement or clarification.

Compliance Markets

The Amendment Act primarily focuses on carbon trading, as outlined in section 23 C, which results from; (i) bilateral or multilateral trading agreements, (ii) public-private agreements, or (iii) the voluntary market. The Amendment Act does not, however, provide a framework for other forms of carbon markets such as compliance markets. Compliance markets play a vital role in overseeing carbon credit trading. Their omission raises concerns about the Amendment Act’s adaptability to various carbon market models, hindering Kenya’s ability to fully harness the potential of diverse market mechanisms for carbon credit trading and emissions reduction.

Development of a Local Trading Market

The Amendment Act positions Kenya primarily as a source of carbon credits and offsets trading overseas and does not expressly create mechanisms or propose specific interventions toward the development of domestic carbon trading markets. Ideally, Kenya should look to promote the creation of a local voluntary carbon trading framework. The local voluntary carbon trading market is a critical component of intergenerational equity and equitable sharing of accrued benefits with Kenyan citizens and participants in the economy.

Carbon Credits Prior to the Amendment Act

The Amendment Act does not address carbon projects and credits traded under the Kyoto Protocol’s carbon market landscape. There are no transitional mechanisms for dealing with reductions achieved before January 1, 2013, and those registered prior to that date. In addition, the Amendment Act does not address issues concerning (i) previously used emission credits, (ii) emission reductions achieved in violation of human rights and without free prior informed consent, and (iii) carbon projects with substantial negative social and environmental impacts. The lack of transitional provisions under the Kyoto Protocol’s regime raises concerns about the Amendment Act’s ability to address past carbon market projects and their implications.

Benefit Sharing Framework

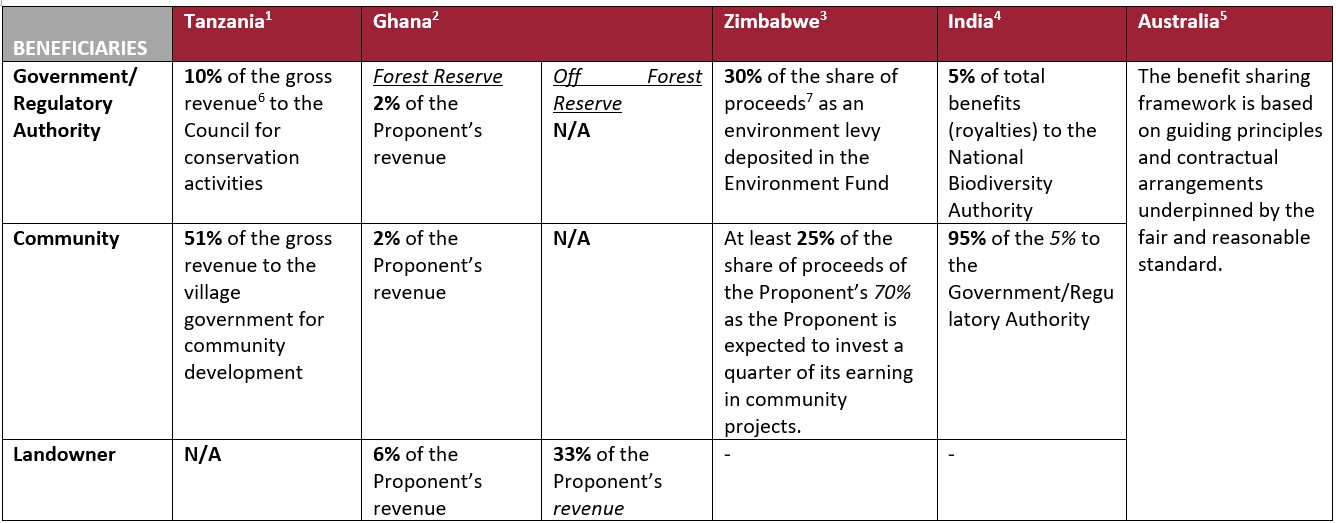

The Amendment Act introduces a mandatory requirement for a substantial percentage of project revenue to be allocated as annual social contributions. It also mandates an additional contribution by providing for the sharing of “benefits” with impacted communities. Noting the Amendment Act’s prescribed annual social contribution of 40% or 25% to the community, in relation to land based or non-land-based projects respectively, as well as the inclusion of the sharing of benefits with impacted communities, the benefit sharing framework under the Amendment Act may be considered high compared to global averages.

In addition, the Amendment Act does not provide defined mechanisms for implementing this benefit-sharing requirement. Consequently, the specific approach and framework for distributing these benefits to affected communities remains undefined and unclear. This ambiguity may create difficulty in the practical implementation and effectiveness of the benefit-sharing provision, leaving room for potential uncertainties and future disputes regarding the equitable distribution of benefits among impacted parties.

Benefit Sharing: High Annual Social Contributions to the Community

As illustrated below, the Amendment Act’s annual social contributions and benefit sharing arrangements are higher than contributions in several other jurisdictions, which risks disincentivising project proponents from investing in carbon projects in Kenya. We have provided a brief comparative view of carbon projects benefit sharing frameworks in other jurisdictions and the typical ratios project proponents are expected to contribute to various stakeholders in other jurisdictions:

Lack of Clarity on Carbon Standards

Carbon standards are crucial for certifying that carbon credits are legitimate and have a meaningful impact on reducing emissions. Though the Amendment Act makes reference to the use of carbon standards, it does not specify a particular carbon standard that should be applied in accreditation and certification. Additionally, the Amendment Act mentions that carbon offset projects should prevent emissions from entering the atmosphere for a ‘reasonable length of time’. However, the Act doesn’t define what constitutes a ‘reasonable time’ in this context. This lack of clarity creates ambiguity, consequently, creating difficulty in determining the authenticity and reliability of carbon credits. The lack of clarity with respect to carbon standards may also increase the risk of “greenwashing,” a practice where the environmental benefits of a product or project are exaggerated or falsely claimed. Furthermore, there may be a risk that carbon offset projects may not deliver the environmental benefits they claim to achieve, undermining the overall effectiveness of efforts to combat climate change that are enshrined in the Amendment Act.

Mandatory Referral to the National Environmental Tribunal

Any dispute concerning land-based or non-land-based projects, which has not been resolved within 30 days from the dispute being lodged should be referred to the National Environmental Tribunal (the Tribunal). This mandatory requirement to refer disputes to the Tribunal after 30 days fails to consider the complexity of the disputes which may arise from the nature of the carbon project and the reality that because of the multiple stakeholders involved, disputes are likely to require more than 30 days for the conclusion of a fair and equitable decision.

The mandatory referral to the Tribunal should only be a last resort requirement for the disputes that have not been resolved enabling the stakeholders to select the dispute resolution mechanism that best fits their arrangement. The requirement that the disputes should be referred to a local Tribunal limits the options available for the international investors that have significantly borne the project’s costs and risks which is likely to disincentivise the Proponents to setup a project in Kenya.

Community Interests

In the interest of safeguarding intergenerational community interests and upholding the constitutional right to sustainable development while allowing for flexibility for different types of carbon rights projects, the Amendment Act should specify the minimum requirements or guidelines for protecting community interests that are to form part of each carbon project plan.

Additional Compliance Requirements and Related Costs

Under the Amendment Act, every carbon trading project is required to obtain an Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA). This requirement appears excessive, as not all carbon projects will meet the criteria under the Environmental Management Coordination Act (EMCA) for mandatory ESIAs. In our view, only those projects that would otherwise by their nature have been subject to EMCA should be required to obtain an ESIA. The projects that would not otherwise be subject to an ESIA under EMCA should not be subjected to such a process through the Amendment Act as doing so will drastically reduce the ability of the proposed carbon mechanism to effectively reduce, remove or avoid emissions across the targeted sectors in line with Kenya’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) targets.

The costs associated with the mandatory assessments and certifications can result in carbon trading activities within Kenya becoming cost-ineffective, with the financial burden imposed by these requirements outweighing the potential benefits of engaging in carbon trading in the country.

Conclusion

The commercial potential of Kenya’s carbon market will be further maximised once the country has addressed the shortfalls posed by the Amendment Act. Failure to address these shortfalls may result in reduced investor interest towards the development of carbon reduction projects in Kenya hence ultimately creating a roadblock for the achievement of Kenya’s NDC targets through voluntary cooperation.

Should you have any questions about this legal alert, do not hesitate to contact Dominic Rebelo or Wangui Kaniaru.

______________

Contributors

1. Kimberly Mureithi – Associate

2. Fenan Estifanos – Trainee Lawyer

3. Sharon Muoki – Trainee Lawyer

______________

Footnotes

[1] Section 34(2) of the Environmental Management (Control and Management of Carbon Trading) Regulation, Tanzania, 2022. The percentages indicated above are the divisions where there is no Managing Authority.

[2] Ghana is in the process of developing their benefit sharing framework under REDD+, however, there are several benefit sharing regimes that are already in place. Above is the ‘Commercial Private Plantation Revenue Sharing’ framework adopted by the Ghana Forest Commission accessed on https://www.forestcarbonpartnership.org/system/files/documents/FC%20BS%20Final%20Report.pdf .

[3] Section 12 and Seventh Schedule of the Carbon Credits (General) Regulations, Cap 20:27, Zimbabwe,2023.

[4] Biological Diversity Act, 2002 and the functions of the National Biodiversity Authority (NBA), India.

[5] Benefit Sharing Framework, Clean Energy Regulator under the Australian Government accessed on https://www.cleanenergyregulator.gov.au/ERF/Want-to-participate-in-the-Emissions-Reduction-Fund/Step-4-Delivery-and-payment/managing-a-contract/benefit-sharing-framework.

[6] A definition of gross revenue is not defined under the Environmental Management Act (Cap.191), Tanzania or the Environmental Management (Control and Management of Carbon Trading) Regulation, Tanzania, 2022. The meaning gross revenue is taken to be the total revenue earned before deduction of expenses and losses.

[7] Share of proceeds under the Carbon Credits (General) Regulations, Zimbabwe, 2023, is defined as the aggregated amount of gross proceeds a project proponent receives upon the sale of carbon credits.